The 2024 Bi-National People’s Tribunal on the Struggles of Farmworkers in North America

November 2024 – Food Chain Workers Alliance

Executive Summary

On March 30, 2024, a historic tribunal took place at The People’s Forum in midtown Manhattan. Fourteen current and former farmworkers presented testimony on behalf of themselves and their fellow workers, reporting on conditions they face working in dairies in Vermont and New York; in greenhouses in Ontario, Canada; and on farms in Massachusetts, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Washington. Video messages from workers in Vermont and Jamaica were also shown.

Over the course of sessions focused on Health & Safety, Freedom of Movement, and Climate Justice, farmworker leaders spoke about life-changing injuries, abysmal housing, sexual assault and harassment, heat exhaustion, social isolation, employer retaliation for organizing, and other everyday realities for agricultural workers.

This tribunal was organized by the Farmworker Committee of the Food Chain Workers Alliance to unite and amplify the voices of farmworkers across North America and beyond. Because our current systems do not function to provide justice for farmworkers, testimonies we heard at the tribunal must be answered by collective organizing at the grassroots level.

Nothing has changed. And that’s why this is so important, that’s why it’s so historic, because to my memory, in the forty plus years that I’ve been a revolutionary, this is the first farmworker tribunal that I know of, and that I’ve attended.

Jaribu Hill, Mississippi Workers’ Center for Human Rights

This is a historic moment for farmworkers. I can’t remember the last time or the first time there’s ever been a gathering like this of farmworker organizations from all around the U.S., from Canada, coming together and strategizing and building this analysis together. Usually we’re isolated, we’re just doing the work on our local level or state level, never coming together like this on an international level, to discuss what does a farmworker movement from the grassroots really look like? And how do we build power from the bottom up?

Edgar Franks, Familias Unidas por la Justicia

Why a People’s Tribunal?

Tribunals are set up to shed light on unheard cases of human rights violations and are activated at the request of social forces.

Tribunale Permanente dei Popoli

Rather than courts and other judicial apparatus set up by states, organizers instead convene jurors from around the world to adjudicate.

Azadeh Shahshahani

People’s tribunals are forums of justice set up by social movements, communities, and organizations to bring attention to the truths with which our judicial and political forums either cannot or choose not to engage. Although people’s tribunals have little authority beyond the integrity and respect generated from the process and participants, they shed light on and amplify human rights violations, as well as a vision for addressing those violations. There is a long history of people’s tribunals used by movements across the world to expose systems of oppression while building accountability, including:

1967

The International War Crimes Tribunal (aka The Russell Tribunal)

1974 – 1976

Peoples’ Tribunal on Repression in Brazil, Chile & Latin America (aka Russell II)

1979

Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal is established and has since convened for judgments on 52 issues including the Armenian Genocide, the policies of the IMF and the World Bank, the Iraq War, Palestine, the Murder of Journalists, & more

2013

First annual Farmworker Tribunal in Washington State, organized by Community to Community Development and Familias Unidas por la Justicia

2019

Tribunal of New York Farmworkers to pass the Farm Laborers Fair Labor Practice Act in NY, organized by Rural & Migrant Ministry and the Worker Justice Center of NY

We have workers across the world, farmworkers from across the world to listen, to organize, and to shame our governments. We’re also here to say that we’re going to be organizing outside; we don’t need to engage in legislative reforms. It’s about building workers’ power, collective power, across the food chain.

Chris Ramsaroop, Justice for Migrant Workers

Organizing the Tribunal from the Bottom Up

Members of the Farmworker Committee — who organize with agricultural workers in Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Washington, and Ontario, Canada — worked with their own members to support workers to present their own testimony at the tribunal, as well as written testimonies of their colleagues.

Development of testimonies happened largely between January and the March, 2024 over the course of nine virtual listening sessions co-facilitated by FCWA staff and worker leaders from Alianza Agrícola, The Farmworker Association of Florida, Justice for Migrant Workers, Pioneer Valley Workers’ Center, and Workers’ Center of Central NY.

Listening sessions generated much more information than could be included in the tribunal and were therefore helpful not just to prepare testimony, but also to support member organizations in developing their base building and forming deeper connections with their members.

Because tribunals operate outside of oppressive power structures, it is only fitting that they operate differently than those structures. We took a bottom-up approach as much as we could, leaving it to workers themselves and worker-based orgs who sit on the Farmworker Committee to do the planning, with oversight and logistics support provided by FCWA staff.

Local & International Political Context

Around the globe, hundreds of millions of food workers make it possible for the world to eat. Almost all the food we eat passes through the hands of workers who plant, harvest, process, package, transport, prepare, sell, and serve. As detailed in our report No Piece of the Pie: U.S. Food Workers in 2016, in the U.S. alone there are more than 21.5 million workers along the food chain, making the food industry the largest employer. It’s also one of the most exploitative.

Food workers receive the lowest median wage of any working group and they are also more dependent on public assistance. They are subjected to dangerous working conditions with high rates of injury, death, and illness. They are also greatly impacted by climate change, from rising temperatures in the fields and workplaces to climate disasters such as wildfires. These conditions, along with increasing precariousness and a lack of job security, leave food workers vulnerable to wage theft; racial, ethnic, gender discrimination; sexual harassment; and violence.

We organize with the knowledge that our food and labor system is rooted in a history of slavery and colonization that continues to shape conditions today. We understand that in order to dismantle institutions of labor exploitation we must also dismantle institutions of racism and colonization. Likewise, global capitalism and imperialism in the form of economic violence, war, and militarization of our cities and borders also strongly shape these conditions.

A common thread of the testimonies and discussions heard at the tribunal points to the ways that farmworkers in North America have been directly impacted by these global systems, especially in the context of forced migration into the exploitative North American labor supply chain. We believe our struggles must always reflect this analysis and build global solidarity.

This tribunal also took inspiration from larger grassroots farmworker and peasant movements that have challenged capitalist agricultural systems across the Americas and around the world. The farmworker members of the FCWA are politically aligned with local and global social movements that fight not only for better labor conditions, but also for a different relationship with the land. One that is based not on exploitation, but global justice; land autonomy; and food, cultural, and political sovereignty.

While the political context in the U.S. and Canada may be different from other countries, the intense farming methods and continued marginalization of farmworkers is much the same. So are the uncompromising principles of organizing. Women farmworkers in Bangladesh and members of NayaKrishi Andolon (fighting for a sustainable agriculture and against the transnational agroindustry that is altering seeds) sent a video message of solidarity to the tribunal that speaks to the commonality of global farmworker struggles:

We are in solidarity with you who are organizing in North America, we wish all of your demands to become true, we wish that the tribunal be successful and that all the companies that are contaminating our world be hold accountable

FCWA Farmworker Committee

Farm labor, including the dairy sector, is a key part of the supply chain, and grassroots farmworker organizations have been part of FCWA’s leadership since its founding in 2009. These members are fighting for the right to organize and other basic protections through workplace, community, and policy campaigns. They include one of the first independent farmworker unions in the U.S. and several worker-based centers implementing worker-driven social responsibility models like Milk With Dignity in the Northeastern U.S. dairy industry. They take on issues like heat stress, the right to overtime pay, livable wages, livable housing, and systematic racial discrimination. They lead campaigns like the fight for collective bargaining rights in New York and the fight against racist discrimination in Canada’s guestworker program.

In 2019, FCWA farmworker members began to work together as a committee. One of the first collective projects was opposing the Farm Workforce Modernization Act, a federal bill that was branded as offering a path to legalization for farmworkers. In reality, this bill would set a long and complicated path to residency status that is tied to exploitation. In 2023, after failing twice, the bill was introduced for the third time, and we continue to oppose it.

Also in 2019, farmworker members worked alongside other FCWA members to build our food worker platform and principles that center worker leadership, global justice, racial justice, migrant justice, gender justice, climate justice, bread and roses, cross-sector solidarity, food sovereignty and building alternative economic systems.

In 2023, the Farmworker Committee engaged in its own strategic planning process to build on the FCWA platform, establishing the tenets that serve as a baseline for our collective work in the sector:

- Canada and the U.S are imperial actors.

- Our food system is a capitalist system.

- Our food system is structured on racist principles that affect everything.

- Agriculture is used as a tool of repression.

- We build solidarity between Black, brown and Indigenous workers to beat “divide and conquer” tactics.

- No borders will separate us.

- We center worker leadership and experiences.

- We center disability and climate justice.

That strategic process also led to the creation of this tribunal, a key step in our effort to build a collective analysis, narrative, and vision for our movement going forward. Currently, there is no national or bi-national alliance of farmworkers putting forward such a vision, so there is a critical need to fill this void and counter harmful narratives by industry groups and corporate-backed politicians, as well as continued efforts to block unionizing and organizing. Through the tribunal and ongoing collective work, FCWA farmworker members are creating a vision of farmworker justice and a new grassroots farmworker movement.

Session One: Health & Safety

Introduction

In the Health & Safety session, five women panelists shared their own stories and brought forward the voices of many others. Video testimonies from several men who were not able to be with us in-person were also shared. At the top of the session, Julie Dragonetti, an organizer from the Worker Justice of New York (WJCNY), provided context on what we mean when we talk about health and safety:

For farmworkers, a lack of safety can be anything from lack of training and personal protective equipment, exposure to pesticides and other dangerous chemicals, long hours without rest, poor living conditions, or a hostile or even abusive work environment.

Testimonies in this session spanned a range of concerns, from dilapidated housing to lack of basic facilities, hazardous working conditions, and sexual violence. Some things that stood out about this panel in particular were that all in-person panelists were women, and there was a pronounced focus on sexual violence and the wellbeing of children.

Housing

In a 24/7 industry like dairy farming, employers normally provide on-site housing for workers. Maira, a former dairy worker and organizer with the Workers’ Center of Central New York (WCCNY), spoke about the dangers and hazards of farm housing:

The biggest problems are pests, lack of space, broken windows, no heating, no privacy, failure of machines such as washing machines and refrigerators. The lack of privacy and cleanliness is what affects people the most, especially families.

Workers are forced to live in crowded spaces with broken appliances that they often have to replace themselves. There is often a misconception that only adults and mainly males live in farm housing, but employers do allow workers to have their family with them, so spouses and children are sometimes living there as well. Maira explained:

The homes are not safe for children, but the employers accept children because they need the workers to be stable, and to not leave the farm easily. A worker without family and children is more likely to leave the farm. Many are grateful to be allowed to have a family there, but the truth is that the bosses exploit the situation.

Maira also shared stories from her colleagues who have lived in this type of housing with their children:

Children have to be locked up, they cannot be children. Not only because there is no space, but because these homes are dangerous: broken windows, cockroaches, etc. Our children cannot be children. This is almost not talked about… There are times when we are so desperate that we have to seek help from allies, teachers, etc. because the bosses don’t care… Is the employers’ fault for not providing safe housing.

Migrant Justice (MJ) sent in a video testimony from dairy workers in Vermont showing their housing conditions: multiple beds in one open space with plywood on the walls, no windows, and bed frames that are rusted and not secure.

Bathroom Access

Even when farmworkers are not living in employer-provided housing, they still suffer from a lack of sufficient and/or working facilities. Claudia, a former farmworker and Director of the Pioneer Valley Workers Center (PVWC), spoke about a chronic lack of bathroom access that is not only inhumane in the short-term, but can also cause long-term health problems. This is particularly difficult for women because the lack of facilities means that they have to walk further away to be able to relieve themselves with relative privacy:

One of the most serious health and safety problems is the lack of toilets in the fields. Not only they are far away, but we have to walk a lot to get to the bathrooms. Sometimes they are very dirty… The main problem is that you don’t have time to go because there is always a supervisor rushing.

People working under extreme temperatures are forced to abstain from drinking water because they are pressured to keep working at a high speed, and get reprimanded for taking care of their basic needs. Workers are left to deal with the long-term consequences without any help from the employer:

A couple of women workers had to go to the hospital because they couldn’t wait to go to the bathroom because they got a urine infection. The doctors told them to drink enough fluids, but they told them that they were restricted from going to the bathroom at work and that they couldn’t drink water for that reason. None of the workers wanted to tell the boss because they knew that he would not pay attention to them.

Workplace Injuries

Due to a lack of adequate health insurance, fear of immigration authorities in hospitals, and employers that deny workers’ compensation, workers in Canada and the U.S. are rarely able to rely on the healthcare systems despite the fact that they often incur injuries on the job. Testimonies on this subject strongly suggest that such injuries are not isolated incidents. Moilene, an organizer with Justice for Migrant Workers (J4MW), shared multiple stories from workers in Canada:

I fell from over 9 feet and was stuck with multiple injuries. The employer knew the doctors at the hospital. They had friends at the workers’ compensation board and they had friends in the liaison office, so [I] had nowhere to turn.

When I got an injury at a pumpkin farm, one of the employees called the boss and told him that I got injured. [The boss] didn’t really come there quickly… I told him I was really really dizzy and not feeling good. The only thing the boss wanted me to do was go back to work. He didn’t ask me if I wanted to go to the hospital. He didn’t bring a first aid kit or anything. He just wanted me to go back to work.

Workplace accidents range from falling from high places to injuries from animals and exposure to pesticides. Yesenia, a dairy worker receiving services from WJCNY, shared her experience:

A cow got scared and pinned me against the tubes, damaging my back. She pressed me all against the tube and was stepping on my feet. The cow didn’t move, and I couldn’t move my arms. The cows weigh about 400 or 500 kilos. No one helped me, there was an American worker who ignored me. I turned around as best I could and as safe as I could. It lasted about a minute. I thought I had completely broken my body. I couldn’t walk, I didn’t call 911, just texted the boss. The only thing he said to me was: ’Did this happen at work? Who is going to cover you? Do you have someone to cover you?’

J4MW also shared video testimony from former workers in Canada’s guest worker program, now back home in Jamaica. They shared experiences of getting injured on the job and struggling to get support from Canada’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB):

I was at work and we were traveling on a bus and the bus hit a pothole. I bumped up… I landed back down flat and injured my lower back, so now I’m just here living with a spinal injury. When the WSIB cut my benefit, I felt like it was a disaster struck me, you know? I didn’t know what to do, where to turn… I just lost my only source of income, I started to think about where I’m gonna get food… for my rent, my light bills. Financially to send my kids to school and so on. So it was a landslide, you know?

After lunch the tractor overturned. That’s where I fell and got a broken knee, also three slipped discs. The WSIB cut my loss of earning and say that I could work in Ontario doing customer service work. When they cut my benefit, I just come in like a fish out of water, don’t know what to do… You have to borrow money from friends and family to go to doctor… no money to buy medication.

Another video testimony was sent in by Jesús, a dairy worker with MJ in Vermont who realized one day that the tractor he was using was not in working order. Unfortunately, that did not prevent him from getting a life-altering injury:

I reported it three times that day, but nobody listened. So this is what happened to me at the end of the day. You can see my foot is bandaged. Now I have an appointment at the hospital and I’m worried because I have diabetes. They’re going to be amputating part of my foot now. I want you all to know that not everything is good on these farms, like they say. You can report machinery [as broken] and they won’t listen.

Sexual Violence

Claudia and farmworker members of PVWC testified that sexual harassment of farmworkers is not talked about because it mainly affects women. Women have reported being touched without their consent while they sleep, being raped in their rooms, being offered better work schedules in exchange for sexual acts, being harassed and threatened while they are working, and having their weekly pay withheld by supervisors unless they agree to go out with them. Patricia, a former farmworker and organizer with PVWC, shared a specific incident related to her by a comrade:

When the other woman left, she was the only one among 13 men. The boss had a room where there was no door for her, the room didn’t have a door, only a curtain. There was a man who, when she came home from work, she was tired and went to sleep, this man would come and start touching her. She felt desperate and stayed still, because many times he was drunk… It is an unbearable memory for her. She asked the boss if he could put a door with a lock in her room so that wouldn’t happen, but he never did.

Patricia also shared her own experience:

I started working on a farm where a man who was in charge made a lot of advances toward me and told me that he wanted to go out with me. I told him that I wasn’t interested. At night he sent me messages that he wanted to go out with me, and I told him no. And he told me ’I have your check, if you want it, you will accompany me out one day.’ At the end of the week, he paid everyone except me… He told me one day ’you think you’re too good for me? Don’t you know that I can make you lose your job?’

The stories shared in Patricia’s testimony emphasize the conditions that make sexual violence torward women take place, whether it is poor housing with no privacy or isolation in the fields. Patricia also talked about women not going to the employers to complain either because of language barriers or because they are afraid of no resolution and retaliation from the person abusing them. However, there have been cases where women fight back. A co-worker shared with Patricia:

That is why I came to this organization to become an organizer for all the abuses that occur in the countryside. When I was chopping the vegetables, sometimes the manager intentionally touched me like my buttocks. I was bent over working, and that made me so uncomfortable and angry. I went to talk to the boss, but the boss told me that he had never had any problems and no complaints about the supervisor, that it was only with me. At that time I didn’t know about organizing collectively, I couldn’t organize other women until now after I learned about this organization. Then things changed for me.

Reflections & Discussion: Fighting for Safety

In the jurors’ reflections and discussions with panelists, they noted that the employers, governments and corporations that benefit from farmworker labor are directly to blame for these problems. The working conditions described are not a simple oversight, nor are they isolated incidents; they are the norm. The way that agribusiness has organized farm production is the direct result of a system rooted in colonization: workers are expected to produce as much as physically possible under precarious and vulnerable conditions.

However, testimonies also showed that workers are resisting these unjust conditions. As part of the closing remarks, Fabiola Ortiz Valdez from the FCWA said:

Everything that you mentioned is a small window showing us what you go through, but even this small window is enough to reveal one of the most severe contradictions of capitalism: the bosses need your bodies, they need you healthy to work, and at the same time they are not only indifferent to your wellbeing, but they purposely create and maintain the conditions to keep their workers vulnerable. And also all of us here recognize that you shared examples not only of the collective campaigns that you have all participated in, but also all the individual acts of resistance.

Even with nowhere else to go, women find ways to leave farm housing that is not safe for them or their families. They make hard decisions to take legal actions against powerful and well-resourced employers. They confront supervisors and demand clean housing with working appliances. They talk to other workers about shared conditions and experiences. Women workers also look for the support of outside organizations and build their own political education to pursue, what Patricia called their right “to be happy, to smile, to talk with whoever we want without being harassed.”

Sexism and machismo on the farms may not be the bosses’ fault, but they do benefit from it. This keeps the workers divided. Perhaps that is the strategy of maintaining a group of weak workers… We all deserve respect. When they have women working, they have to be protected, we run more risks than others.

Claudia, PVWC

As somebody who is a believer in human rights over civil rights… you have to go to the bathroom, that is part of being a human being… you’ll never hear out of my mouth, as much as I practice human rights, that I’m a human rights defender. I’m a human rights enforcer. The fact that we live and we’re human beings, we enforce those rights that are intrinsic to us.

Rob Robinson

Solidarity and love to you from sisters who are going through the same thing you’re going through in the Mississippi Delta: bathroom rights or lack thereof, having to wear Pampers — or now Depends since those have been invented. Before Depends people used to take a Pamper in the front and a Pamper in the back to keep from soiling themselves… In fish plants and chicken plants in Mississippi, they still do not have bathroom rights.

Jaribu Hill

If I close my eyes, everything that you said harkens back to farmworkers in South Asia, particularly tea workers in Bangladesh. Women who are raped, women who can’t use the bathroom, women who work until their last minutes of pregnancy; miscarriages… It can’t be by accident that Mississippi and Bangladesh have such similar stories.

Chaumtoli Huq

Session Two: Freedom of Movement

Introduction

Freedom of movement is a critical demand for farmworkers across all regions and sectors. In his opening remarks, facilitator Chris Ramsaroop from Justice for Migrant Workers (J4MW) harkened back to the term plantation economy to describe the systems of indentureship that are based in employer control over farmworker bodies. This plantation economy requires the restriction of workers’ movement in order for individual growers to profit and for our capitalist food system to be sustainable. Testimonies told us how employers take advantage of workers’ immigration status and exploitative legal frameworks to control them, as well as how workers are resisting.

Collaboration Between Immigration and Law Enforcement

Luis Jiménez, a dairy worker and co-founder of Alianza Agrícola (AA) stated that while we often think of the South when we imagine border regions, New York is also a border state where border control is omnipresent and workers are at risk of detention. The collaboration between Border Patrol and the police means that for workers there is little distinction between the two. When workers organize, employers threaten to call the police, and by extension, immigration. Combined with the fear of losing jobs and housing, the fear of immigration control is one of the biggest barriers to organizing.

Luis also shared that under the Trump Administration, bosses restricted workers’ movements if they did not have a driver’s license, for fear of workers being detained. He went on to say:

But this does not mean that the bosses are good people and want to protect us, but rather that they do not want to be left without workers. On the contrary, we will never see bosses fight for a permit for us, or for immigration reform. With a work permit we would be more independent, we could organize ourselves more easily, or we could look for another job more easily. The bosses don’t want to lose control, they will never advocate for a permit for us, but they will advocate for the expansion of programs like H-2A.

After extensive organizing, workers in New York won the right to access driver’s licenses regardless of immigration status in 2019. Luis shared that this has been one stepping stone to freedom of movement for farmworkers in the state:

For us, winning the right to have a license was difficult, and even though it was a victory because some people have lost some fear, the reality is that it is not the solution to the problem, the fear continues. Thanks to collaboration and participation of many allied organizations supporting our work, we have been able to achieve many changes in the community to protect agricultural workers, the immigrant community, but I think we should have more freedom.

Juan, a worker leader from CATA also testified about undocumented farmworkers living with the constant underlying worry of deportation:

It is like a threatening giant that makes people psychologically ill. It is believed that half of the agricultural workers do not have the documents that protect them. Therefore, we have lived in the shadow of fear. In the current administration, thank God, we have lived a little peacefully, but we have not stopped worrying because we know that later on our peace of mind will be broken again and fear will invade us again in the fields, at home, on the street, wherever we go.

In the meantime, we will continue to maintain our hopes that one day, politicians will come to an agreement and give us at least a work permit to mitigate the permanent fear of deportation, which would suddenly stop our progress towards achieving our goals.

Laws and Legal Frameworks that Restrict Movement

Juana, an organizer with The Farmworker Association of Florida (FWAF), described how recent laws in the state are escalating attacks on farmworkers and migrant workers and amplifying fear in their communities. She stated that one of the most dangerous elements of these laws is how they limit freedom of movement. Under SB 1718, for example, licenses from other states are no longer valid in Florida and E-Verify has been made mandatory in workplaces with more than 25 employees. In her written testimony, Juana described how the modification of this law to only apply to new workers has had an impact on existing workers who lack immigration status:

First is that many people were fired and many people do not have jobs for the same reason, many people left, but above all it is that many people have had to stay in jobs that perhaps are not good because they are not going to be hired in other farms. So the people who are at work cannot leave and look for another job because they are going to use E-verify. This is a way to ensure that employers do not run out of workers, and that the workers have no choice but to stay. If they are treating you badly, you can no longer leave because you don’t know if they will hire you for a job elsewhere. This is an advantage for employers who are abusers, they tell us ’If one day they leave, they can’t come back.’

She shared that as new restrictions are introduced, growers are increasingly using the exploitative agricultural guest worker program H-2A:

Growing the H-2A program benefits the industry because workers are tied to an employer. Sometimes they even take away their passport, also limiting their mobility and work options. It seems that this law in a certain way wants to create the same situation for undocumented immigrants, the gain comes from limiting movement: they want to restrict movement, make them stay there and not be able to go out to look for better work. It seems that this is what they want to do with everyone, migrants and H-2A.

Alfredo, a farmworker and organizer with Community to Community Development (C2C) in Washington described how workers are organizing to oppose the expansion of H-2A in the state. Through their work with farmworker communities, C2C and Familias Unidas por la Justicia (FUJ) have seen the impacts on guestworkers and local farmworkers and their families. The H-2A program relies on an extreme form of employer control wherein workers are isolated, have their passports seized, and cannot exert labor mobility.

People are moved from their home to a place they don’t know to work a lot of time under extreme conditions without proper equipment to stay safe. There is a lot of wage theft. They usually don’t have any connection with other people that live around the place where they stay. The company that brings them here holds on to the worker’s passport, at any point that those workers do things that the company doesn’t like they — the workers — can get deported at any time. They could be put on a blacklist where they can’t apply to work at any company in the U.S. ever. H-2A workers don’t know their rights. Those that speak up are threatened with being deported. Because of this H-2A workers stay silent.

Alfredo added that even though hiring H-2A workers costs employers a lot of money, companies would rather use the program than pay local workers a better wage because of the control they have over a tied workforce. He shared that this impacts local workers too, because

The company is making us compete with our brothers and sisters in the field for work.

Companies claim they have a labor shortage and must use H-2A workers to meet their needs, while making it very difficult for local farmworkers to apply to jobs and reducing the number of hours given to local farmworkers.

A lot of companies claim that they will go bankrupt if they pay local workers more. The reason these companies go bankrupt is because of bad investments, and a huge reason is the big companies buy small companies, which make it harder for small companies to compete. In my 12 years as a farmworker and as an organizer I have never heard of a company go bankrupt because they pay and treat their workers better.

Gabriel, a former migrant farmworker and organizer with J4MW shared multiple testimonies from guestworkers in Canada’s Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, as well as his own experience in the program. These stories show a similar situation to migrant workers in the U.S., including a tied work permit that creates a huge power imbalance between workers and employers. As Gabriel put it, “the employer is not just our employer, they control every aspect of our life, the employer is our landlord, the employer is our travel agent.” Another J4MW member described it as “this is like having a dog on a leash.”

Our documents are being taken away from us and they can book our flight back home in a minute. They keep our passports. We are told we cannot leave the compound unless they take us. You can only shop where they choose to take you, and sometimes the food is expired.

A testimony from another worker leader from J4MW encapsulated many workers’ understanding that small changes aren’t enough to address this power imbalance:

The entire system has to change. The whole colonial system they have in place has to be taken out completely. Everything has to change from the top. Because of the government’s unjust laws and policies, it has given employers the legal right to just treat us however they feel because it is legal to do so. They know that they won’t be held responsible for what they’re doing. We’re not called by our name, we’re called by numbers. We’re not seen as people. We’re seen as animals. We’re seen as something else. We’re seen as broken. If you’re seen as broken you’re thrown out. If you speak up or say something, they consider you to be unruly or a trouble maker and immediately, they will book your ticket to fly you out… We need status on arrival because with status, we can access everything that we need, on our own. We need to access healthcare and everything else that we need.

Workers with J4MW described how their longtime organizing demand of status upon arrival means freedom of movement:

Status is very important because that will hold employers accountable for better treatment. They will know that you now have the power and can leave whenever to work wherever you want — they can’t control you anymore. You’re not tied.

Reflections & Discussion: Building Unity, Naming Those Responsible

Facilitator Chris Ramasaroop recalled that the FCWA Farmworker Committee has led the opposition to harmful legislation like the Farm Workforce Modernization Act, which moves in the opposite direction of freedom of movement. He asked participants to think about how the demand for freedom of movement lays out a vision for organizing and movement-building in which “no one’s immigration status should be used against them, to think about it as a way to try to bring people together, to take away the power of bosses to divide workers, and the use of threats and fears to try and subjugate and subordinate workers.” In the discussion, jurors and participants also reflected on the importance of sovereignty over land and naming who benefits from workers being immobilized:

I would love for you guys as you go forward to talk more about, not living on the land of these ranchers or farmers… but controlling that land. There’s more of us than of them so we have to change that dynamic. I’m not sitting here and pretending that it’s easy, but we have to understand that control of land is what we’re struggling for here.

Rob Robinson

Can we get a role call on some of the companies that are directly responsible for global suffering in the U.S., wherever people languish under the system of U.S. imperialism? Can we get a roll call on some of the corporate dogs who are grinding us into the ground and destroying our opportunities in this world? … If we don’t denounce and indict those corporations, we’re not really doing the serious work.

Jaribu Hill

Those who are responsible for our working conditions are the big corporations who benefit from our labor, the corporations who buy the products we produce. These corporations haven’t wanted to pay attention to the workers who are behind their products.

Luis, AA

He who controls land controls food. He who controls your food, controls you. What did COVID teach us? Increasingly the food system is in the hands of a few people.

Gabriel, J4MW

What all of you have shown through the guest worker program, is that actually it’s the law itself that is exploitative. So then how do we use it… but then how do we actually dismantle it, because it keeps us in this plantation economy?

Chaumtoli Huq

The injustices are the same across the board. In my opinion the workers who don’t have freedom of movement [in our sector] are the undocumented workers who have been working in these warehouses for decades, and also our brown and black brothers and sisters who are coming out of incarceration. Both of these groups, they’re staffed by staffing agencies… These groups don’t have the freedom to work where they want to work or seek different jobs. These groups are in the same struggle but they are also pinned against each other at work.

Adi, Warehouse Workers for Justice

Session Three: Climate Justice

Introduction

In the months leading up to the tribunal, FCWA members from all sectors held a preliminary conversation to discuss what climate justice means for food workers. Participants were clear as to the urgency of the crisis and the fact that climate and environmental justice cannot be separated from worker, migrant, racial, and global justice.

We are already witnessing not only the degradation of the planet and our food systems, but the short-term and long-term degradation of the health and livelihoods of workers and their communities. Conditions of agricultural labor, including dairy, force workers to be exposed to extreme temperatures and climate disasters like hurricanes and wildfires, as described by testimony in this session.

Workers receive little protection from these dangers, and when they try to intervene in the workplace on behalf of their health or the health of others, they are met with abuse and retaliation. Organizer commentary in this session paints a broad picture of the challenges for farmworkers in this new reality and the systems that make intervention more challenging.

Testimony

Edgar Franks is an organizer with Familias Unidas por la Justicia (FUJ) in Washington State, where there is significant agricultural production and farmworker organizing. Edgar opened the session with a story that demonstrates agricultural workers’ vulnerable position in this new climate reality. A group of H-2A workers employed on a farm near the Canadian border contacted FUJ to report that they were fired after holding a work stoppage. Edgar recounted:

We traveled up there and were met with 100 workers, standing together with their suitcases not knowing what to do.

Days before the work stoppage, one worker was having health issues. He had diabetes and was working in the extreme heat of the Pacific Northwest’s recent heat waves. Workers alerted the employer, but not only was he not taken to a hospital or given medical assistance, but the employer even denied him a break. Only after he fainted did they take him to seek help. However, it was too late, and before he could be seen he suffered a stroke and died.

On top of the labor abuses, workers had to deal with the extreme heat, smoke from Canadian fires, lack of water, lack of breaks, etc… that combination created CHAOS. Climate Justice has to be part of labor organizing.

Extreme Temperatures

Many of the testimonies in this session revealed the very real ways that workers are currently being harmed by extreme temperatures, including cold temperatures, as well as the consequences for trying to alleviate that harm:

At work it was so hot, I could see the heat wave. I passed out more than once from the heat that was there. I don’t know what happened. I think by that time the ambulance came there, and they said nothing. Everybody just got back to work. You’re not allowed to take water in the field. You can’t get access to your things if you need it. Other people had fainted as well. You just had to do what the employer said.

Worker testimony read by Moilene, J4MW

I will never forget one day when I was picking blackberries, it was a very hot day, close to lunchtime I heard people yell ’Help! Help!’ Someone passed out in the row, I ran to see who it was. It was my sister.

Alfredo, C2C

Many people stay silent to keep their jobs. From May to August the temperatures are almost unbearable, we are talking about 100 degrees or even 105 degrees, and the pace of work is more intense.

Ivan, FWAF

OSHA may have regulations for high temperatures, but the cold is also extreme for some industries like dairy. Many people may not pay as much attention to the cold, but it should be taken into account. The work is more complicated during the winter. What you do in the summer in half an hour, in the winter it takes you about an hour or more. We are sometimes in open places where the air is very aggressive. Maybe those who don’t milk the cows don’t realize, but those who milk know that the floor can freeze, the machines freeze and you have to put your hand in hot water and that affects us. The accidents that happen due to low temperatures are: blows, people slip, your bones hurt, you can’t breathe. The water would freeze inside, the workers have to buy their own portable heaters, and so you have to find a way to stay warm.

Ismael, AA

The rules, the laws that govern workers are not written by workers. They’re written by the bosses and big companies. Even though global warming and climate change affects all of us… it affects each of us in different ways. Rich people, they can go somewhere cooler, a cooler place, they can have air conditioning, they can have all the luxuries so they don’t feel the heat or the cold… But for someone who’s poor and working in the fields, there aren’t many options… The laws that exist are not sufficient or strong or enforced to protect us. We decided to take climate change as a central issue in our union in Washington… It is an issue that is very local, but international at the same time.

Edgar, FUJ

Climate Disasters

In 2023, some of the biggest wildfires in recent history took place in northeastern Canada. Farmworkers there, as well as in the Northwest and Northeast regions of the U.S., reported that the fires created a greenhouse of smoke right at the time when temperatures were already increasing. One aspect of the testimonies and similar stories we’ve heard from workers in other food sectors is the total lack of information and personal protective equipment (PPE). Emergency disaster plans, whether for a fire, hurricane, or pandemic, often exclude workers completely.

We didn’t have masks. Our eyes were watering, tearing, burning. I gave out masks from my house. They didn’t care. After 2 days of poor air quality they gave us masks but not good ones. We never stopped working. At the beginning we didn’t know what was happening, we got really scared, we kept working under the orange fiery sky, everytime we heard someone coughing, we told them to take a break, workers don’t know they have the right to take breaks.

Ismael, AA

Forced Migration

Climate change and environmental destruction is facilitated by colonial and imperialist systems, which leads to the forced migration of many of the people who migrate to the U.S. and Canada and end up working in the food system. The exploitative supply chain begins at the point of forced migration.

Many of my community is here due to indirect or non visible displacements by the oil industries, since the land where we are from is rich in natural resources that make the world run and that enriches a country or the landowners. But at the same time that is no longer our land, we are not from any of these parts — we were displaced. The land became increasingly dry and not very fertile; the water and air were also contaminated. That is rarely mentioned or it is silenced with money without mentioning the irreparable damage in the future that will lead to the possible massive displacement of an entire town.

Enrique, MJ

At a time like this we need to talk more about the violence that keeps capitalism going, just as extreme if not more than revolutionary violence.

Edgar, FUJ

This is not the place I thought it was, it’s not what people claim it is. There is a history of oppression in this country.

Ismael, AA

Reflections & Discussion: Organizing for Climate Justice

The discussion that followed worker testimonies focused on solutions and accountability. Many of the testimonies had already mentioned the importance of union and community organizing.

What we want to see change is that our working conditions improve. We want to see workers be allowed to unionize.

Worker testimony read by Moilene, J4MW

The state of Washington has heat rules protections for outdoor workers, but that is not enough. The trigger temperature for the heat rule is 80°F, but that is too high for us, it needs to be lower. The trigger temperature should be 75°F. Most of us work at a piece rate, this means we get paid for the amount that we produce. If we want to make more money we have to work hard and faster. This causes our body temperature to be really high, so the trigger temperature needs to be reduced to 75°F.

Alfredo, C2C

Participants also looked at broader questions about the future of farmworker and food worker communities overall. Juror Chaumtoli Huq posed the question: “Is our vision that we will always be workers under capitalism?” This led to a broad discussion on the value of building worker cooperatives as a model for the future. Workers participating in the hearing had different perspectives:

It’s hard to build a cooperative, almost all the land [in our area] is owned by ranchers, they don’t want to sell land to migrants. The land is also contaminated and it’s hard to find land where we can plant organically. Yet we are still trying and struggling to build this.

Ismael, AA

Community to Community was able to establish a cooperative that is run by workers. It’s possible, but a lot of work is needed.

Alfredo, C2C

Witnesses, audience and jurors discussed the vision of changing the agricultural system to one that is cooperatively held, in order to move away from the exploitation of waged labor under capitalism and build a food system that does not degrade the earth and contribute to the climate and environmental crisis. Pointing to the Landless Workers Movement in Brazil, juror Rob Robinson recalled how that group organized and reappropriated land for 600,000 families: “The way we relate to land needs to fundamentally change.”

Toward a Farmworker Organizing Vision

Over two-hand-a-half hours of testimony we heard from dozens of workers, both in-person and virtually, sharing their own experiences and those of their comrades. These accounts show how our profit-driven food system relies on the hyper-exploitation of agricultural workers and all food workers. Immigration status, gendered and racialized discrimination and abuse, wage theft and basic human rights on the job, isolation — all of this creates severe disadvantages and precariousness that allows for exploitation to continue. For many farmworkers, their employer is also their landlord, so if they lose their jobs, they lose their housing. Living at work also increases workers’ isolation and surveillance. Testimonies and discussions during the tribunal raised several key points:

Existing Legal and Political Structures will not Lead to Justice

The current legal and political systems are not sufficient to protect farmworkers from exploitation. We must find ways to work outside these structures and/or dismantle them for our liberation. At the same time, workers know that it’s important to continue to engage and challenge our legal and political systems. For example, by legally challenging states for lack of protection and discrimination like CATA’s case in New Jersey and J4MW’s multiple cases in Ontario, and by creating new laws that will improve worker protections like WCCNY’s and AA’s fight for historic legislation in New York.

While policy victories and legal strategies can be tools that workers use to their advantage, they are not enough. The very governmental systems that are supposed to protect workers more often benefit employers, who employ them to continue a legacy of exploitation.

The Canadian government has been stealing money in the name of WSIB, taking EI — that’s employment insurance — from migrant workers since 1966, starting with the Jamaican workers, knowing that there’s absolutely no way that it could ever be claimed… Canada finally admitted that they were stealing. Let’s say it in black and white. They were stealing from workers all this time.

Moilene, J4MW

If the government agencies were actually doing their job, the workplace situations would be a lot better. People would have clean water at their job. And the bathrooms would be clean.

Juana, FWAF

Building Sovereignty: The Land Belongs to Those who Work it

We cannot exert control as a working class without gaining some control over land. The question of a “good boss” or a “bad boss” is irrelevant, because all employers will strategize ways to keep workers from organizing. Workers are the only ones that know what a just workplace looks like, whether that means better and enforceable labor protections or changes in production. Collective ownership, such as the creation of worker-owned cooperatives, is one way to eliminate the hierarchical relationship between employer and employee, and allow workers to implement their own knowledge of how to work the land.

Alianza Agrícola, we are in the process of forming and developing our own cooperative. It is very hard in the area where we are because all the land is occupied with ranches, so it’s very hard to find good land for cultivating… The Americans don’t want to sell ranches or land to migrant people. I don’t know why.

Ismael, AA

If you control the land, you control water, you control food.

Rob Robinson

Empire & Colonization

It is impossible to untangle any of the abuses described in worker testimonies from the violence that was central to the establishment of the U.S. and Canada: chattel slavery, genocide and oppression of indigenous people, and stolen land. The reason farmworkers are federally excluded from some basic rights that other workers in the U.S. are afforded, for example, dates back to their exclusion from the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act. That law was passed just seventy three years after the end of the Civil War, when most agricultural workers in the country were Black.

All of our comrades [on the panel]… have come from countries that have been plundered and ravaged by this empire. So you don’t have the same relationship to the land. Indigenous people had a relationship to the land here, but they were murdered by genocide and their land was taken… The land you are working on is almost like modern day sharecropping. When I think about my ancestors sharecropped, and we call that crop without shares, where you are working the land of the oppressor, making the profit of the oppressor, here in this country working on the oppressor’s land.

Jaribu Hill

Gender Justice

It is not possible to achieve farmworker justice without addressing and eliminating systemic abuses based on gender. Women are vital for the agricultural industry, not only for production but often for the social reproduction of the labor force living on farms with their families (cooking, cleaning, caring for children etc). Women experience health and safety and other violations in specific gendered ways. When sexual abuse or harassment happens in the workplace, the employer can benefit when workers become further divided and afraid. Women’s labor and knowledge of the workplace, migration and climate change are vital for organizing in the workplace and beyond.

Centering Worker-Led Organizing

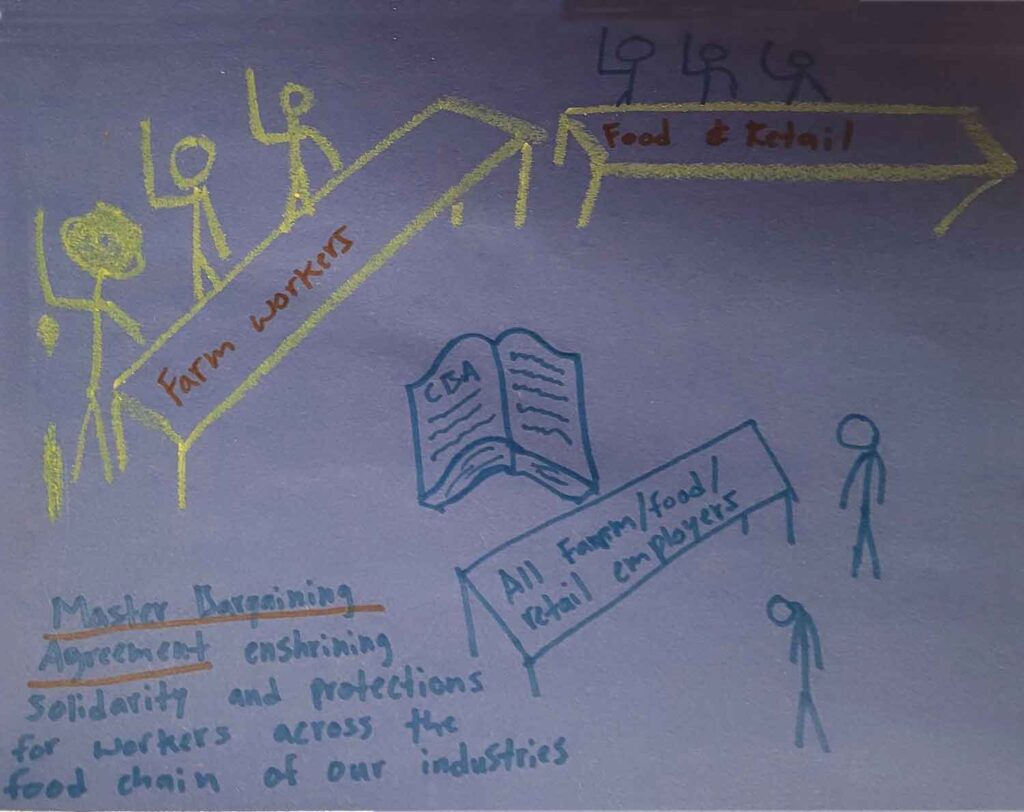

Our organizing will be stronger if we center the following principles and/or strategies:

- Worker Solidarity in the Face of Division

Divisions between workers based on immigration status, race or ethnicity are often created or amplified by employers, who benefit when workers are not united. We must prioritize building solidarity across all workers in a workplace and/or sector. - Supply Chain Analysis

We must look outside our sectors. All workers in the food system can build power and leverage by connecting up our fights. At the tribunal, warehouse and restaurant worker organizers made connections between issues raised by farmworker leaders and issues in their own sectors. - Building Power across the Industry

How do we go beyond organizing farm by farm? How can strategies like sectoral bargaining support workers to bring rights and power with them into every workplace? - Transnational Vision

Global capitalism is driving down wages and working conditions across the world. Transcending borders and organizing across continents is critical. - Naming Those Responsible

Our organizing must have a clear-eyed view of the power structures and players who are responsible for violations and injustices and maintaining the status quo.

If you go to a restaurant… you’ll notice that at the back of the house are Black and Brown people who in different parts of their lives worked in the fields. When you talk to a worker as an organizer you hear their stories… you see the quite literal scars of the working conditions from where they previously worked. The other thing that see is the fear… that what the boss says is inevitable and is the end of the story. [But] I want to leave us with a little bit of hope: just as fear permeates everything… one hand washes the other, and solidarity is also a virtuous cycle that can take effect… These employers are not all powerful. They may think so, they might be able to convince you that they are, but they are not. Solidarity wins out, numbers wins out, hope does win out.

Mark Medina, Burgerville Workers Union

Envisioning Liberation

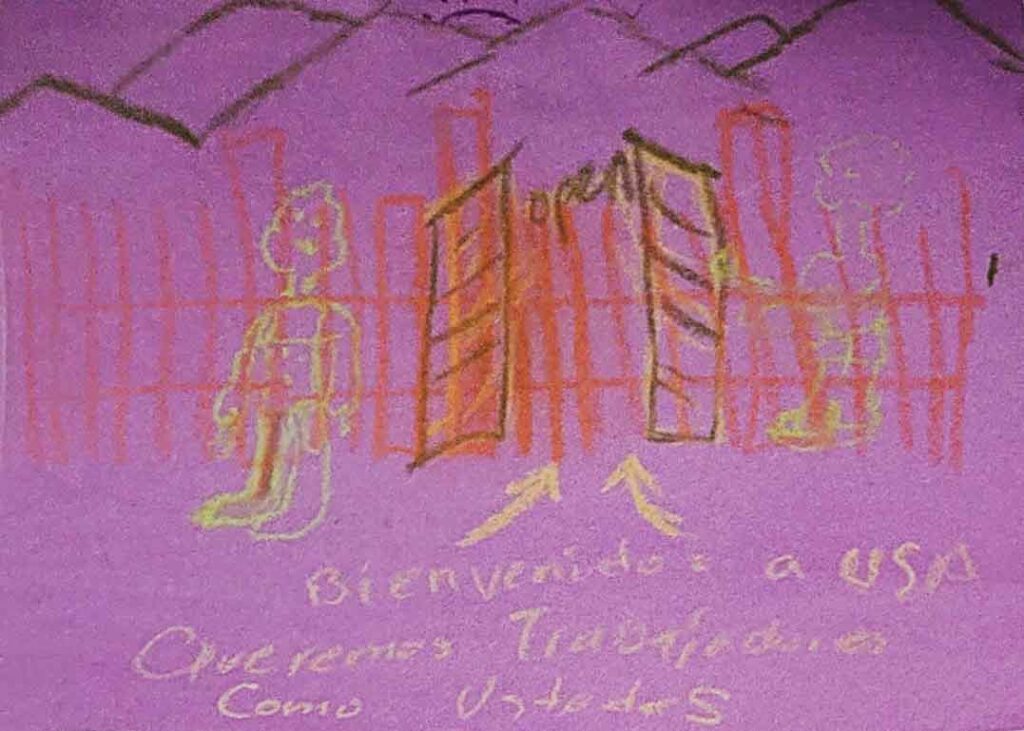

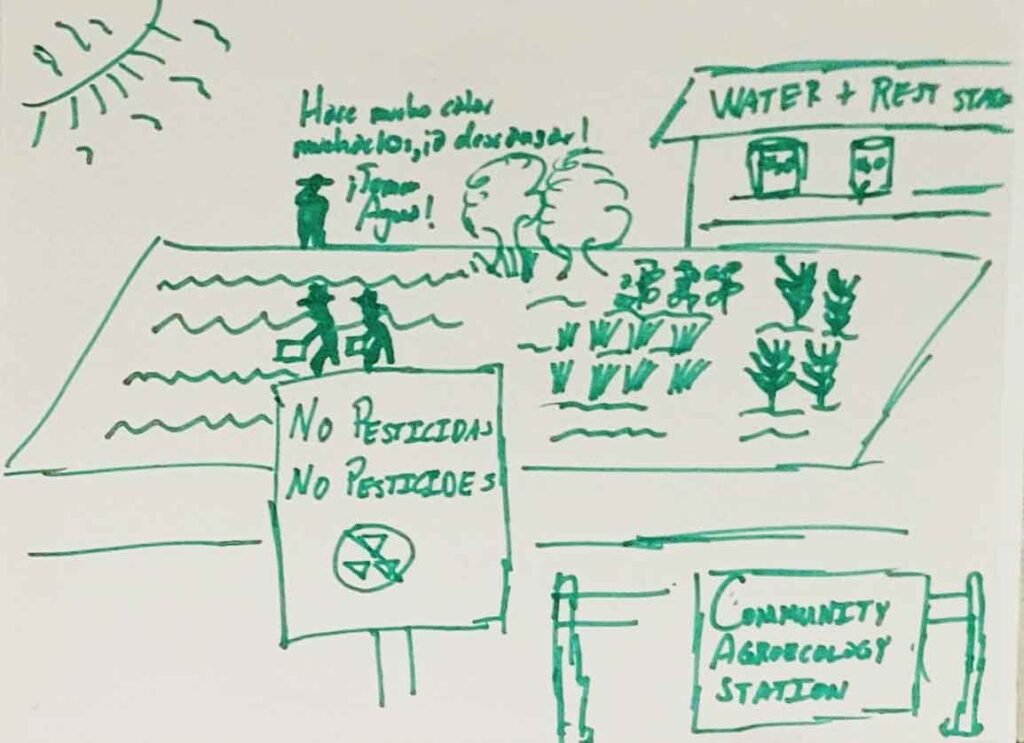

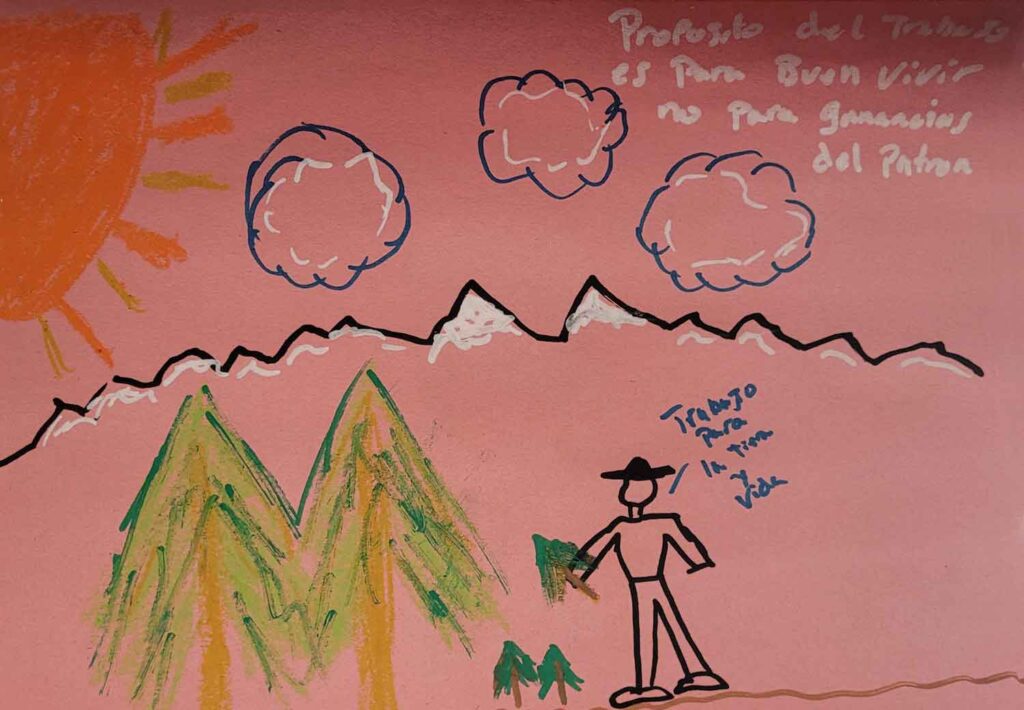

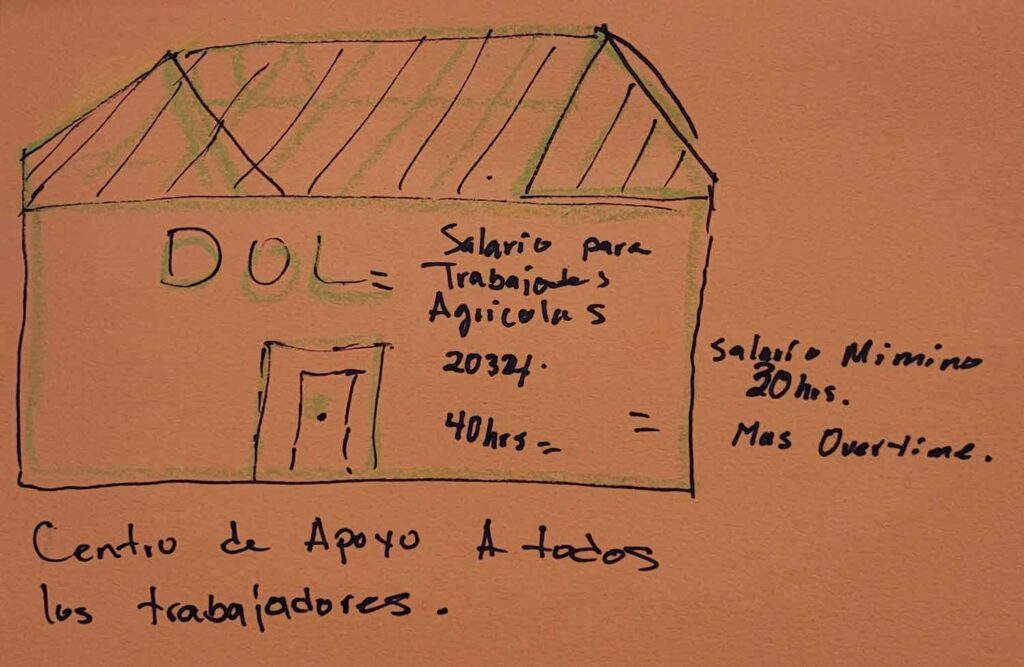

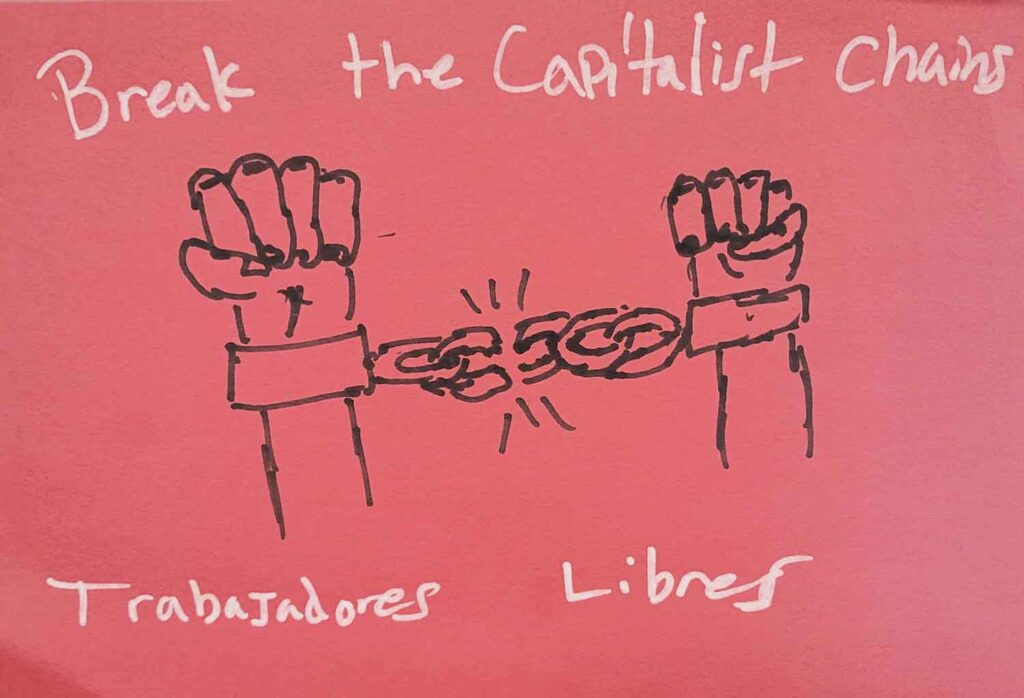

The day before testimonies were shared, all tribunal participants met in a closed session to envision a just future for farmworkers. Workers and organizers created art expressing their vision and presented their works to the group. This was followed by a group discussion to find commonalities, differences, and strengths; and identify needs and plans for the future. A powerful picture of farmworker justice and liberation emerged, in which:

- Food and agricultural systems break the chains of capitalism and are centered around community and cooperation.

- Families are together and happy. There is no more ICE and there are no more border walls. Immigrant workers are not living in fear; instead they are welcomed.

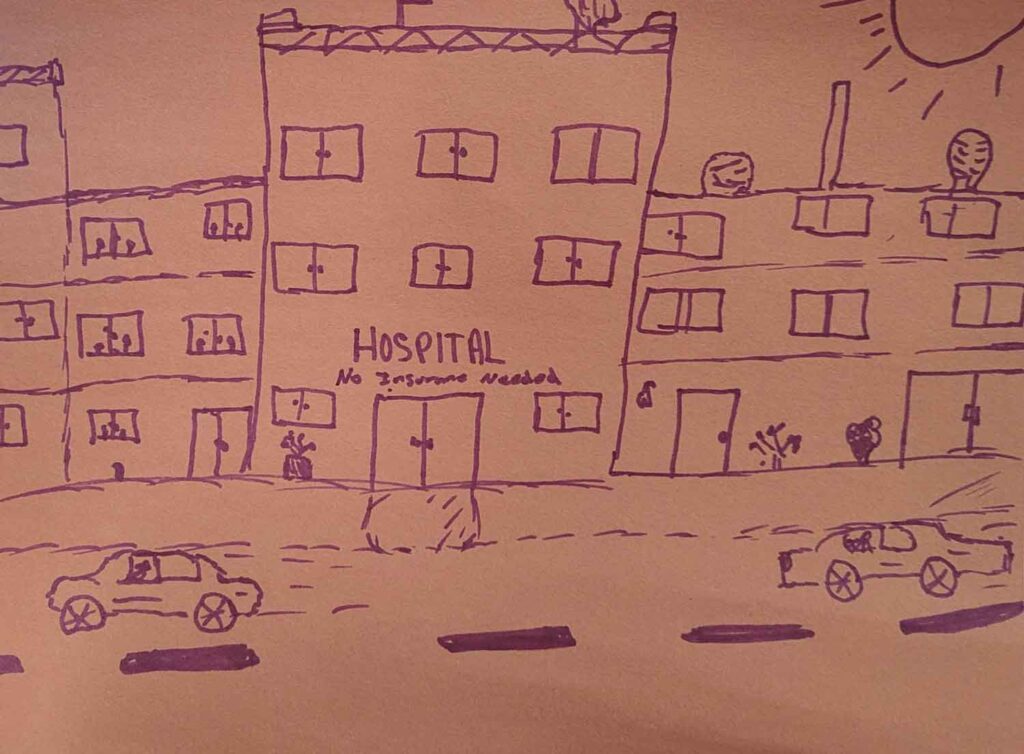

- Farmworkers don’t have their health and lifespan robbed by work, they are not poisoned by pesticides and other chemicals, and there is access to free healthcare for all.

- In communities where farmworkers live, children have access to schools and adults have access to support centers to file claims, get training, and build political power. Communities are not polluted by agribusiness, but are healthy places to play, work, and rest in peace.

- Community agroecology farms and coops abound, where people work for life and earth instead of for profit for the few. Instead of selling labor to a boss, workers share ownership of land and production.

- Our environment is protected and workers are protected from the impacts of climate change and climate disasters.

- Farmworkers unite with other food workers to create shared demands and negotiate collective agreements.

- Farmworkers have ample water, rest & shade, safe conditions and housing, overtime pay after 40 hours/week, and living wages.

The hot sun, damaging health. Reimagine in ten years: instead of the enemy sun, we use the sun to give us energy. Instead of… destroying forests or ranches… [we] plant trees, plant things that bring life back to the earth… We use the land, we have to replace it as it has always been done. The purpose of working is for well-being, not for the boss’s profits.

We imagine something similar to a workers’ coop, where there is production here but it is not mass production that damages the earth, not mono-culture. Different types of products are being grown for the community, so that everyone can benefit.

We talked about the fact that the life of a field worker in the United States is very short in relation to the entire population. In general, the [lifespan of the] population if they do not work in the field is 80 years old. Field worker life is 50 years old. The work is very intense, it took your life away. Part of that is not having access to healthcare, lack of papers, money… Imagine a hospital or a health center where they don’t ask for your papers, everyone has access to a hospital, it is a human right.

With the stories of their comrades and this powerful vision in mind, members of the FCWA Farmworker Committee are forging ahead as part of a new, alternative movement for farmworker justice.

Watch the Tribunal

A full recording is available on the FCWA YouTube channel, with either English or Spanish interpretation.

Visit the FCWA website and our linktree to learn more about our members and their work.

Acknowledgements

Writing & Production

Suzanne Adely, Fabiola Ortiz Valdez, Sonia Singh, Elizabeth Walle

Artwork

Photos

Edgar Franks, Elizabeth Walle

We offer our sincere gratitude to all the farmworkers who shared their personal experiences and the organizers who gathered these powerful stories.

This tribunal was organized by the FCWA Farmworker Committee:

Thank you to jurors Max Ajl, Jaribu Hill, Chaumtoli Huq, Raj Patel, and Rob Robinson; facilitators Fabiola Ortiz Valdez and Julie Dragonetti, Taneeta Doma and Chris Ramsaroop, and Nezahualcoyotl Xiuhtecutli and Edgar Franks; guest member speakers Mark Medina of Burgerville Workers Union and Adi Alvarado of Warehouse Workers Justice; interpreters Cesar Boc, Henry Boc, and Antonio Tovar; staff at the People’s Forum; and those who worked on audio transcription Amaya Carrasco, Ana del Conde, Quinn Di Falco, and Elizabeth O’Connor. Thank you to the FCWA staff team for all their hard work, and Wildseeds Fund and Emergent Fund for their support.